Scientists have started to deliver on the next innovative generation of medicines for patients, bringing cures for rare disease patients that previously had no treatment options and vastly improving how we treat cancer.

Take Nathan Yates, for example, who has lived his entire life afflicted with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Yates’s parents were told during his first year of life that their baby was unlikely to survive past early childhood. Now 30 years old, Yates has a growing number of treatment options for his SMA, as do others with the disease. The condition, albeit rare, is the top genetic death-causing disease for kids in their first two years of life. The price tag of the latest treatment, Zolgensma, is $2.125M, making it the most expensive drug therapy in the world.

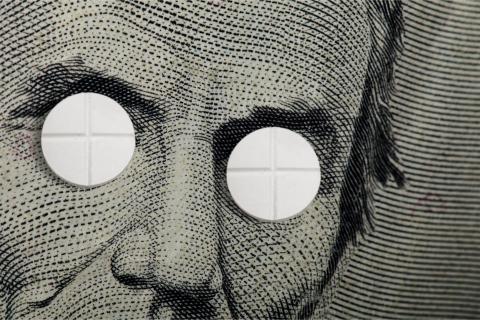

The challenges associated with these breakthroughs to public and private payers are vast. For instance, consider the sheer potential cost for curing something like sickle cell disease, which afflicts an estimated 70,000 people in the United States. A gene therapy cure for this population hypothetically priced at $1M would cost an astounding $70B in total. And while long-term cost offsets are typically realized overtime, patients tend to change health insurers over the course of their lifetimes, meaning that the cost offset to a given payer may never be achieved. While competition eventually brought costs down significantly to cure hepatitis C, a future multi-source environment cannot be relied upon as some rare disorders afflict patient populations that are too small to attract multiple entrants and drug development dollars.

There is industry-wide consensus that the current status-quo reimbursement models are not properly set up to pay for these innovative therapies. Groups have even formed, such as the Paying for Cures focus project at MIT, to bring awareness and solutions to this growing challenge.

So what is the answer? We must restructure the current reimbursement system and develop new payment models to ensure access to these monumental innovations in science. Here we will explore some emerging alternative payment models that just might get us on track to bring cures to patients and allow for continued innovation in drug development:

Risk/Outcomes-based Contracting

The National Pharmaceutical Council defines risk/outcomes-based contracting (also referred to as value-based contracting) as a type of payment model whereby pharmaceutical manufacturers and payers agree to link coverage and reimbursement of medications to the drug’s effectiveness and/or how frequently it is used. Although not yet common, there have been many examples of risk sharing agreements, such as the piloted outcomes-based contract for AVASTIN between Genentech and Priority Health. In this case, rebates were tied to PFS, orprogression-free survival, in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a key endpoint in the drug’s phase 3 clinical trial.

Just how prevalent are risk-based contracts to-date? HIRC has tracked dozens of public announcements, and in 2019, 27% of HIRC’s commercial payer panel indicated that they had at least one risk/outcomes-based contract in-place, up from 13% in 2017. These contracts were most often reported in PCSK9 inhibitors and therapies to treat multiple sclerosis, inflammation & immunology conditions, oncology/cancer, and rare disease.

The appropriateness of risk/outcomes based contracts for emerging gene therapies will depend on the disease and medication itself. HIRC has found through its interviews with commercial payers that these arrangements work best in cases where there are well-defined and measurable outcomes, the process for collecting outcomes data is simple, the financial value of the contract is meaningful, and the outcome endpoints occur within a short, defined period, such as 6-12 months.

Subscription-based Contracting

Referred to as the “Netflix model,” the subscription-based contracting approach emerged in June of 2019 when the state of Louisiana entered into an agreement with Gilead Sciences to pay a flat fee for unlimited access to hepatitis C medications for its Medicaid and prison populations. Previously, the state only offered access to the most severe cases; this deal expands access from 1,100 patients treated the previous year to over 30K by the end of 2024.

In spring of 2019, HIRC queried a panel of commercial health plans as to their interest in a subscription-based contracting model for pharmaceuticals. Most point out that the arrangement between Gilead and the state of Louisiana is a unique situation whereby you have both a cure and a controlled population. Panelists were largely unsure if and how this approach would apply more broadly to private payers with other therapies, but agree it is worth some additional investigation. While this approach may not be appropriate for gene therapy, it represents a creative alternative to the status-quo pay-per-patient model that expanded access to a first of its kind cure to patients, making it worth mentioning.

The Payment Plan Model

The “payment plan” model was first introduced toHIRC researchers through interviews with payers regarding how they intend to manage the pipeline of emerging innovative therapies. The payment plan model is exactly as it sounds - instead of paying for a drug therapy in one lump sum payment, insurers can pay in installments over time.

There are a few examples thus far, starting with SMA therapy ZOLGENSMA (mentioned earlier at a price point of $2.125M). In May 2019, Novartis’ subsidiary AveXis announced that it will offer a pay-over-time option, whereby terms of up to five years are offered. At the time of the press release in May of 2019, AveXis confirmed that they were in discussion with over 15 interested payers. One month later, bluebird bio announced that it will offer five-year payment terms for its blood disorder gene therapy ZYNTELGO to European markets, after offering a similar arrangement for LentiGlobin in the US earlier in the year. Yearly payments are contingent on the drug’s continued effectiveness.

While there are likely some kinks to be worked out with this approach, a payment plan model could address budget challenges surrounding a substantial one-time payment, and could address the issue of patients changing insurers over time, especially if payments were to “follow the patient.”

In Conclusion…

As with many things in healthcare, there is likely no single solve-all solution as every new therapy will require a different set of considerations. In some cases, a combination of approaches may be necessary. For instance, both installment arrangements above are also backed by outcomes-based agreements. And sure to emerge are contracting approaches that we’ve never even heard of before. Just last month, Alnylam announced it will offer a “prevalence-based adjustment” (PBA) for its new RNAi therapeutic for GIVLAARI. In this case, Alnylam will offer rebates to payers if the number of their members with acute hepatic porphyria (AHP) “substantially exceeds current epidemiologic estimates” for the condition.

HIRC will continue to measure payer response and uptake of these emerging contracting approaches and payment models in its 2020 research. Until then, Paying for Cures offers a number of great resources, including its next workshop coming up in March 2020. Maybe we’ll see you there!